The Global Drone Security Network #2

Streamed live on Sep 18, 2020

The Global Drone Security Network (GDSN) is the only event of its kind focusing on Cyber-UAV security, Drone Threat Intelligence, Counter-UAS, and UTM security.

View the full conference: https://youtu.be/vZ6sRr65cSk

FULL TRANSCRIPT: PART 1

Moderator: That’s right. Well David, thank you so much for coming on board and obviously as the keynote talk. We wanted to make sure that everyone understood this is quite an important topic that you’ve had brewing here for a while and that you’ve spent a lot of time researching and trying to deliberate between and it’s a very interesting point of view, both for threat intelligence and incident response and everything in between so we’re really looking forward to it. And for those who don’t know you know, David is the founder and CEO of URSA, Inc. so we’re really pleased to have him on board on the topic of UAV threats to the oil and gas industry. So, thanks so much. You’ve got the last talk of the event and thanks for sticking with us.

David: I’m speaking on what UAVs may pose as a threat to oil and gas and energy industry in general but a lot of what I’m going to cover here really touches on things that you’ve been hearing all day. To set the stage as was said my name is David Kovar, CEO and founder of URSA Incorporated. I had a lot of help from a gentleman named Tim Wright on this. He’s a very well-established aerospace journalist and he has the ability due to his experience to dig into places where I don’t. It was really good collaboration. Different agencies respond better to somebody who’s a journalist and other ones respond better to somebody who’s not a journalist, so we didn’t always get that right. It’s been an interesting journey in that regard.

Let me do the “too long, didn’t read” story here: the threat is real. You’ve been hearing that from various people throughout the day. Many organizations are underestimating or downplaying the threat. That’s not something that we’ve been hearing quite as much but I’ll give you some data to support that particular conclusion. The counter-UAS community is part of the problem as well as part of the solution. This is a difficult thing to say – I am part of that community. But I think that if we all sort of step back and look at what we’re doing and how we’re doing it, there is a certain kernel of truth to this particular statement and this is a great opportunity. This particular group, Drone Sec or other forums for collaboration, are opportunities for us to have discussions about how we can move what we’re doing to be more firmly in the “we’re part of the solution” part of that continuum. My conclusion, my belief, and I think you’ve been hearing it from other people today, is that threat intelligence is important. We need to understand the threat. We need to understand the nature of the actors behind that threat. We need to understand what we’re trying to defend against so we can align what our defenses are with the threat and sharing is, and always will be, a significant contributor to managing the risks associated with malicious use sUAS. Sharing is crucial. This forum is a great opportunity for it. Drone Sec has a platform and I’ll talk about some other ones later in this presentation as well but right now a lot of really important information is stove piped or siloed in various places. Some of that’s behind national security concerns. Some of it’s in competitive “I don’t want to share with my competitors.” Some is tied up intellectual property. Some of it’s just tied up in non-disclosure agreements. Some of it’s just tied up and we don’t know whether we can share this stuff or not but I believe that we’re not doing the national security any service by sort of keeping all that information about what is or is not going on to ourselves and that’s not just a U.S. problem – that’s a national problem for anybody anywhere in the world.

To start off to frame the overall conversation, this is from San Diego National Labs, a paper they wrote back in 2007 and it applies to kinetic and cyber-attacks. And by the way I’ve got 20 years of doing cyber security, about five years of doing incident response, digital forensics, a bunch of things like that. I come from more of the cyber community but I’ve got some kinetic experience security as well. Their statement is that to build the right defense, and the right defense means the ones that is most effective, it also means that it’s cost effective. There are a lot of definitions to what the right defense is but to build the defenses capable of standing or surviving cyber kinetic attack or a drone attack we must understand the capabilities posed by those threats to the government to the function or to the system. We’ve got to understand who the threat actors are, what they’re using to create that threat, and only then can we really start building the right defenses. This particular conversation is about energy infrastructure. You could be protecting pretty much anything but I’m using this particular one.

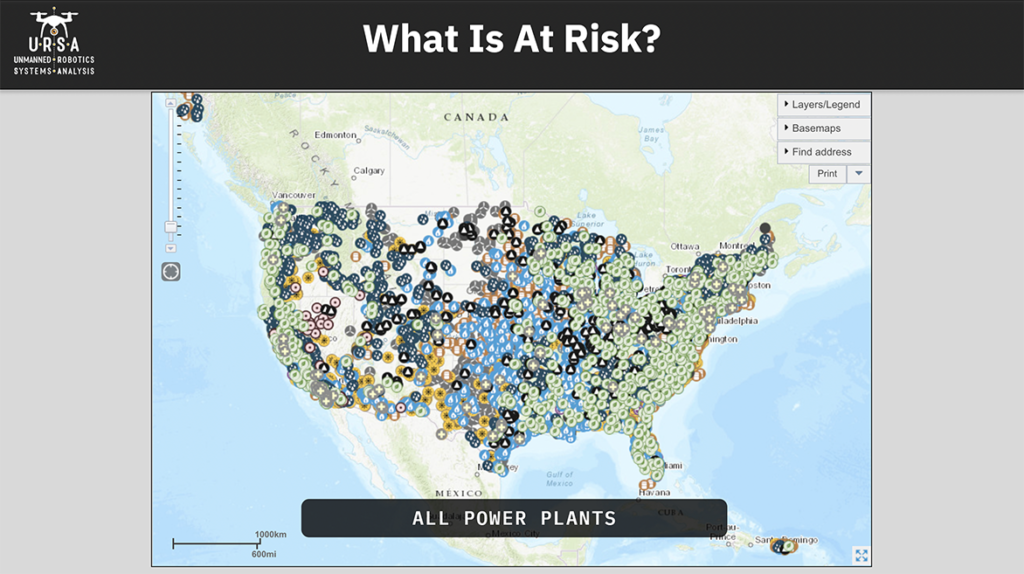

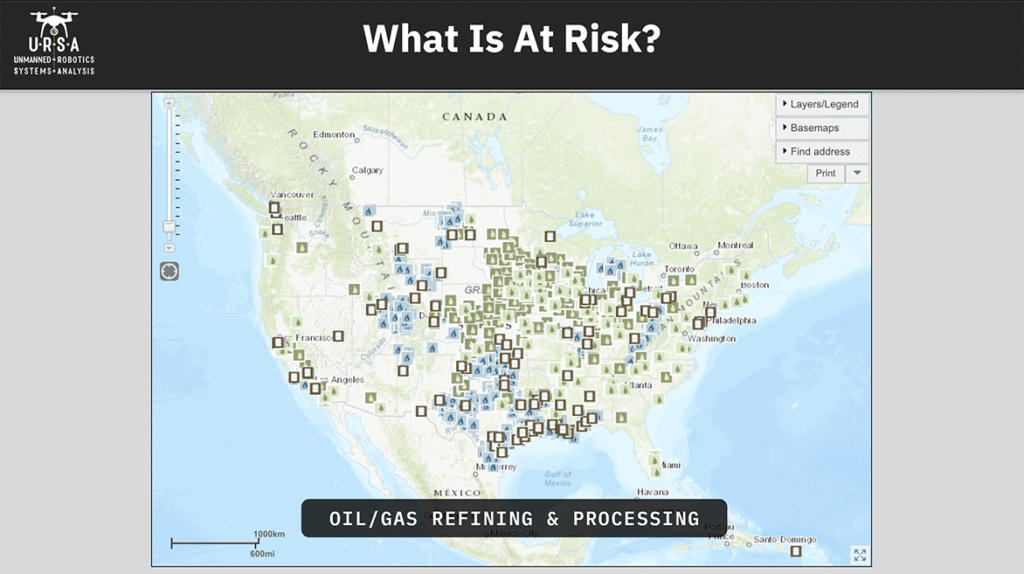

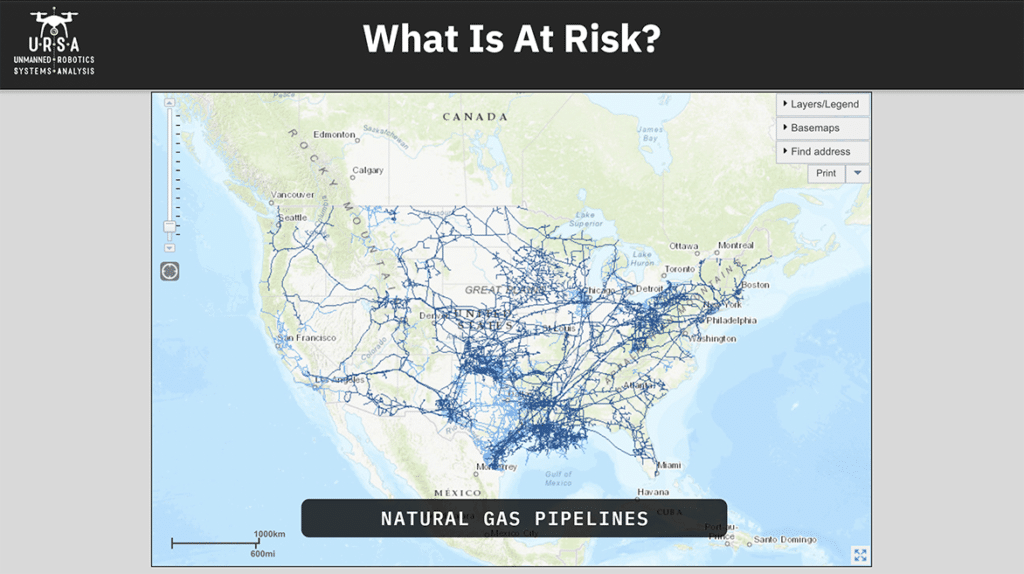

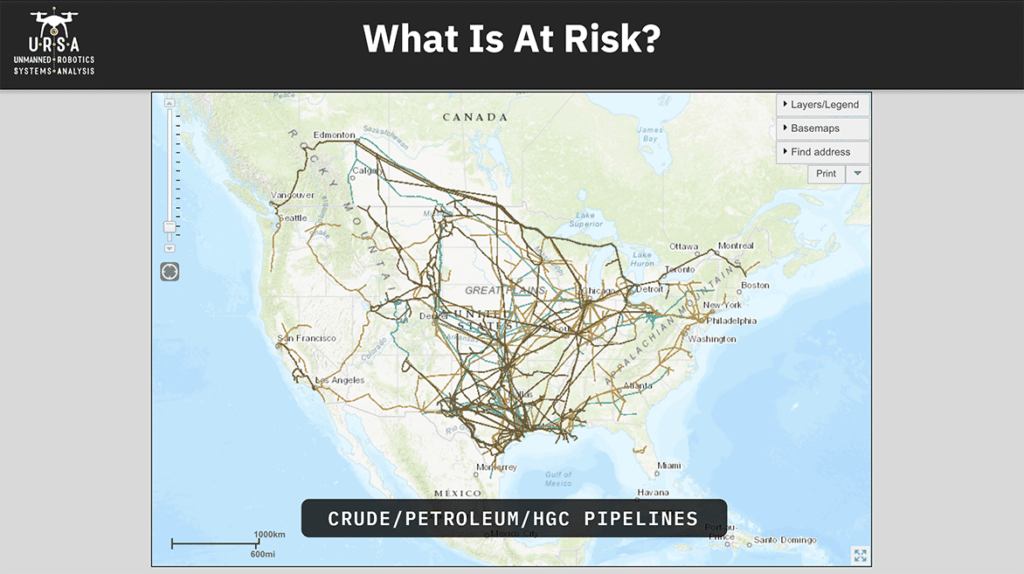

I’m live in New Hampshire. This is just all the power plants in the United States. There’s an awful lot of them and there’s a surprising number of nuclear reactors in here, including one that’s 20 minutes away from my house, which I often times forget. There are an enormous number of oil and gas refining and processing facilities scattered around the country. You’ll notice there’s a lot of the Midwest. I used to drive between Washington, D.C. and New Hampshire all the time and so I’d see the ones in New Jersey. I saw a bunch down in Southern California. There’s a lot of it down around the Gulf Coast and we’ll get to that in a minute. There’s a lot of natural gas pipelines. Thankfully, a lot of these are buried but not all. There’s also oil pipelines and other transmission systems on the surface that are potentially vulnerable, crude oil, petroleum, etc. What’s left out of these graphics is high transmission lines, which are getting a lot more attention after the fire in Northern California last year that was caused by poorly inspected high transmission lines. Those are becoming much more of an area of concern so if the energy infrastructure is the thing that we believe is at risk what is creating that risk in the context of this conversation. We’ve been talking about UAVs and so let’s get down in some specifics.

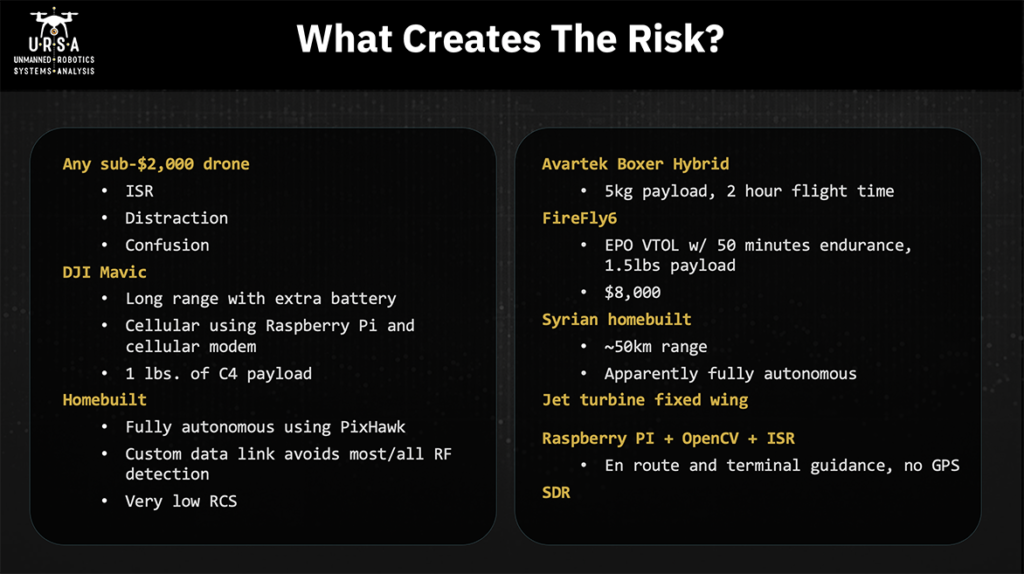

Any sub 2, 000 drone, and I’d even say any sub 1 000 drone can pose a risk for energy infrastructure. They can be used for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. All you have to do is get up there and take pictures with it. They can be used as a distraction. Right now, a drone flying over any sense of facility is going to get some attention and so you can use a 200 or 500 FPV racer, whatever it is. You want to draw the attention of the security forces away from something else that you’re doing or just to see how they’re going to react. And similar to distraction, you can use it for confusion, you can use it to create the perception that something’s occurring that’s not occurring. Getting down to specifics, DJI Mavics – DJI has somewhere between 75 and 85 percent of the consumer commercial market so very popular platforms and they’ve been really popular with a hacking community. People that want to modify these things to get around no-fly zones and to do other things that they were not originally designed to do in the context of posing threat. Some of the things that are getting done with these are making them fly much longer ranges than they’re intended and so there used to be these hacked battery attachments. You can now have two batteries attached. Now people are using 3d printers to make a more professional ability to add a battery to these platforms. A couple years ago somebody put a Raspberry pi with a cellular modem on one and used that for flying longer ranges. Now you can do that with off-the-shelf stuff for non-DJI products and we’ve seen coming out of Mexico, and presumably other places, that they’re being used for delivering malicious payloads. There’s a photograph of one pound of C4 attached to a DJI Mavic. I think that most of us understand that the motivated threat actors are going to be moving away from commercial off-the-shelf products and moving towards home built. There are a variety of solutions or reasons for this on the DJI front. Aeroscope is becoming somewhat prevalent and if you’re going to fly a DJI product there’s a good chance that you can be picked up by an Aeroscope. So easy way to avoid that problem – fly something else. There are some concerns about serial numbers. If you use it for malicious purposes and it’s captured, serial numbers on the UAV could be used for tracing the person who purchases the purchased it back and then showing up their house. Home builds have some really good capabilities that come along with using them. You can make it fully anonymous using Pixhawk or some other flight controller. You can make it shut off the radio the RF link so now it’s now any counter-UAS system that’s complete. That’s dependent on the RF link is going to be blind to them. It can fly on autonomous flight. It can do certain steps during that flight – take pictures, draw payloads, things like that. Then it can turn that RF link back on, if necessary, at certain points during its flight. It’s much easier to use a custom data link. There’s are a variety of counter-UAS systems out there that are looking for specific, what I would call fingerprints, specific types of communication on specific frequencies.

If somebody uses a cellular modem obviously, you’re moving your data link from 915 megahertz well up into the spectrum but there’s plenty of other parts of the spectrum that you could use where somebody wouldn’t see it on the RF. So that’s certainly an option that comes along with home build. Also, you can control what your radio radar cross section looks like. If you’re using an EPO foam fixed wing, your biggest radar reflector is going to be the battery so that gives you control over that more on the commercial side where there are some really powerful platforms out there and we’ve seen some of them earlier today.

The avar tech boxer hybrid is a gas electric hybrid commercially available, has a five-kilogram payload and a two-hour flight time. There’s a lot you can do that with that at a long range. Firefight Six is made here in New Hampshire. DOI was flying it for wildfire purposes before that fleet was grounded. EPO foam, VTOL 50 minutes endurance, 1.5-pound payload. 8 000 is ready to go. It’s also got a really nice sensor that you can say “watch this particular location” and no matter what you’re doing with the aircraft the focus of the eoir sensor will be on that location. So really powerful platform and again for eight thousand dollars pretty much any motivated attacker could go acquire one. I mentioned the Syrian home built. I get tired of people saying, “what you’re proposing is impossible.” The Syrian home build attack on the Russian air base and, I think this is 2018, balsa plywood, gas engine. They supposedly flew about 50 kilometers. There were no GPS units on them as far as I could tell. These things were flying fully autonomously. If there were GPS units on there, there were certainly no radio links and so they were not being manually flown from launch all the way to their target. So, if this could be done in 2018 in Syria what can be done 2020 in the United States? I mentioned jet turbine fixed wing in here. I think they were mentioned in the earlier presentation as well. These things are amazing, very high speed.

There were some components of a jet turbine found in an ISIS drone factory a couple years ago. Nothing functional but you could tell that threat actors were starting to think about this particular platform. If you’ve got a jet turbine fixed wing coming at you by the time that your counter-UAS system detects it and makes some sort of decision even if it’s auto automated in terms of how it’s going to respond to that incursion it is most likely going to be on target. So, the speed is one really interesting characteristic of it. Another characteristic of it is that the explosive payload is the fuel that it is using already. At that speed if it impacts a solid surface that fuel is going to aerosolize and then the motor the impact is going to detonate that fuel. How big is that explosion, it all depends. Raspberry PI plus OpenCV plus ISR. ISR is intelligent, surveillance and reconnaissance. Again, OpenCV is an open source image recognition platform and we know what Raspberry PI is. The combination of these three things gives you the opportunity to do all route and terminal guidance without a GPS, just using optical recognition. And the reason I mentioned ISR is not just because of that all route but if you think about what a petroleum refinery looks like at night it’s got this beautiful color spectrum and all these lights on and things like that and I suspect you would find that those are a very unique fingerprint you can give in a certain pattern light. Say oh I’m coming in from this angle and I’m this far away so that’s where you get your terminal guidance and then one of the other things that’s creating risk and opportunity is software defined radio. We’re using it on the counter-UAS side, but malicious actors are going to use it as well it gives them the opportunity to change their data links to encrypt them. It also gives them the opportunity to use SDR for gathering intelligence about a site and I’ll get to that in a little bit as well. We’re familiar with the group one group, two group, three group, four group, five classification for UAVs. US DOD uses this. NATO uses it as well, some others. It’s a good way of thinking about capabilities in terms of size, weight, payload, endurance, and altitude but as we’re trying to really figure out what’s creating or posing a threat to us or to the sites we’re trying to protect. I really suggest that you think about a sort of broader range of capabilities. This comes from a NASA paper done back in 2010 and it had nothing to do with counter-UAS. It was really just to think about what sort of capabilities there are for UAVs. What some of the interesting ones are here all-weather conditions so you know if you are at a base in the arctic and you’re concerned about UAVs, you’re going to need to have something coming at you is going to need to be all-weather capable. One of the interesting things in here particularly given swarm technologies is the monitoring control multi-ship operation mother-daughter ship corporations so it just gives some examples of some things to think about in terms of capabilities that might be brought to bear on you on your system on your facility.

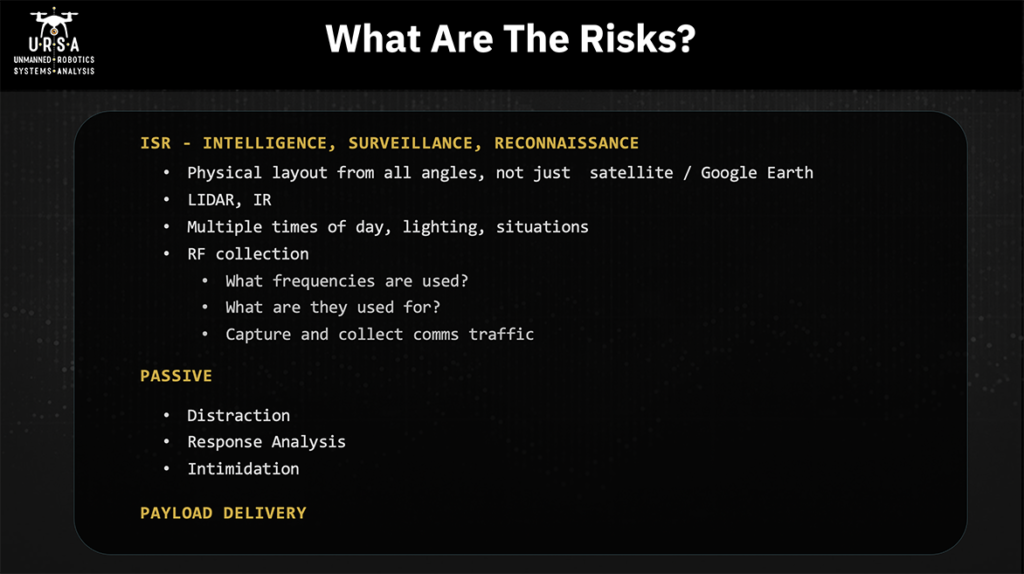

So, we’ve talked about what’s at risk, about what creates a risk. Here are the things that those UAVs pose as risks. We talked about ISR, intelligence/surveillance/reconnaissance. A lot of people when I’ve talked to them about why somebody might use their drones around a security site, and they say “hey, all this imagery is in Google Earth you know. I can just go do it.” Well, first of all, Google Earth the images are taken when they’re taken-you have no control over it. Second of all, all those images are straight down or as close to it as they can get. That doesn’t give you some really valuable information in terms of what the physical layout is looking at it from all angles. It doesn’t give you examples of what the lighting changes when it’s sunset or sunrise. It doesn’t give you information about how people are moving around the facility and things like that. Google Earth is wonderful for doing remote surveillance and reconnaissance but sometime at some point in time in your desire to go effect upon this facility you’re going to want to get eyes on and drones provide a really good eyes on capability.

They can also fly some sensors other than optical. LIDAR can be used if you really want to get into looking at how the facility is constructed down to a very, very fine level of detail and if you’re trying to put a precision trike strike with a small explosive payload on then having that sort of knowledge could be very helpful. IR gives you information about where heat sources are obviously that could be people movement, it could be where generators are, it could be where cooling ponds are, all sorts of things. RF collection doesn’t come up too often but it’s why I mentioned SDR earlier. If you are trying to attack a facility or attack a site, you really want to understand what’s going on with the defense, what are they capable of, what’s their operational tempo like, what are they doing. So, RF collection is one of the things that you would want to do – so what frequencies are they using, what are they using those frequencies for – and can you capture and collect some of that comms traffic. You may fly by capturing that traffic, find out what their shift changes are. If you’re not getting it via other means, you may use this for deciding what to jam when you decide you’re actually going to take action upon the site, things like that. There are passive risks created. We talked about distraction and intimidation response analysis and I’ll talk about the Palo Verde site in a little bit, but these drones were over the site for two days running. The first day drones were over it, you get one sense of what the response looks like. You come by a second time or later it’s like have they changed their response and understanding how the defender is going to react to your various moves you’re going to make is a really important part of preparing yourself and your team for the action you’re about to take and then there’s obviously payload.